The Urgent Need for Low Altitude Awareness in the National Airspace

This guest post by MatrixSpace‘s Dan O’Shea explains the current gaps in airspace awareness technology and infrastructure. This editorial was originally published by DroneLife, January 15, 2025.

The frenzy around December’s drone swarm hysteria in the Mid-Atlantic may have passed but the public panic it sparked highlighted some critical gaps in how the U.S. monitors low-altitude airspace. As drones, air taxis and other forms of air mobility become more common in our skies, it’s clear these gaps need immediate attention.

Since the release of the BVLOS ARC report nearly three years ago and the FAA Reauthorization Act last year, the aviation industry has been making strides toward better electronic conspicuity. Widespread adoption of ADS-B receivers as part of BVLOS CONOPS, and the FAA’s upcoming enforcement of Remote ID requirements promise to improve safety for both uncrewed and traditional aircraft. But last month’s drone swarm panic exposed a glaring issue: we lack the broad infrastructure to properly monitor low-altitude airspace, and that’s eroding public trust in the promise of autonomous and on-demand aviation.

Think about it: with near-universal internet access and public flight-tracking tools, people expect a level of transparency and control. So when reports of unidentified drone swarms over New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and New York surfaced, it understandably rattled confidence in the FAA, law enforcement, and the military to protect Americans concerned about whether they were being spied on, or potentially endangered. For those of us involved with autonomous aviation, the limitations of current airspace monitoring systems like ATC radar, Remote ID, and ADS-B transponders are well understood. But try explaining to the public why a radar that can track a jumbo jet can’t detect a small drone? That’s a tough sell.

Closing the Monitoring Gaps

Even as the industry moves toward solutions like shielded operations and electronic conspicuity, it’s becoming painfully obvious that these are only partial fixes. Gaps in monitoring still exist, and those gaps are vulnerable to exploitation by bad actors—or just human error. For example, Remote ID only works for drones equipped with transponders. RF receivers can’t detect pre-programmed drones operating without a C2 link. And let’s not forget the familiar challenge posed by noncooperative legacy aircraft. These are real issues that leave operators flying blind in too many scenarios.

Conversations with law enforcement agencies in the Mid-Atlantic last month really drove this home. When faced with noncooperative drones—or any unaccounted-for aircraft—agencies were left scrambling, trying to deploy low-altitude tracking technology on the fly. It was a chaotic, patchwork effort that exposed how unprepared we are to handle these situations, leaving both the public and the agencies themselves feeling vulnerable. It doesn’t have to be this way.

This paints a pretty concerning picture, not just for drone operators but for the broader autonomous aviation industry. It’s also a wake-up call for policymakers, local governments, and organizations that oversee critical infrastructure. As autonomous and robotic aircraft become more prevalent in our skies, we need robust, layered systems for low-altitude airspace monitoring that can distinguish between cooperative and noncooperative aircraft. These systems aren’t just about safety; they’re about rebuilding public trust. Law enforcement needs tools to quickly identify legitimate operations versus potential threats. UAS operators need a clear, reliable airspace picture to operate safely. And legacy aircraft operators need assurances that the skies are safe to share. Above all, the public deserves confidence that their privacy is protected and that malicious operators are being tracked and managed.

A Call to Action

This all creates a clear call to action: we need a national infrastructure that integrates a suite of noncooperative detection systems like RF sensors, radars, and optical tools—especially in high-traffic areas, densely populated regions, and along key air corridors—in addition to ADS-B and RID receivers. And these technologies already exist: a number of American companies, including MatrixSpace, are on the leading edge of innovation to support such a safety initiative. To accomplish this vision, though, will require direct investment into our communities from local, state, and federal governments. Investing in this kind of infrastructure now will make our skies safer, build trust in autonomous aircraft operations, create additional economic opportunity within our communities, deter bad actors from exploiting gaps in the system, and support US companies.

Last month’s panic was a warning. We have an opportunity to address these vulnerabilities proactively before a true crisis forces our hand. By investing in comprehensive low-altitude airspace monitoring now, we can unlock the full potential of drones and other autonomous technologies, benefiting industries, communities, and individuals alike—without sacrificing safety, privacy, or security.

Learn more about MatrixSpace’s radar solutions for airspace safety and counter drone detection

Keep Reading

Railyards and rail lines face significant challenges daily—from theft, vandalism, and costly derailments. Technology enables securing their perimeters more effectively while also improve asset inspection practices.

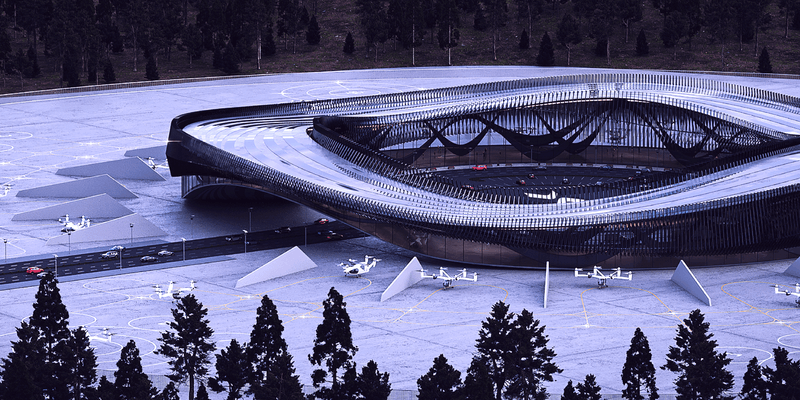

We recently announced a joint venture with Skyway to advance the integration of intelligent air traffic management and uncrewed aircraft detection systems. Skyway develops vertiports and provides advanced solutions for vertiport traffic management and unmanned airspace planning. MatrixSpace provides outdoor sensor solutions leveraging radar technology for use in defense and commercial applications, which addresses this need. The companies’ partnership is intended to support several aspects of enabling practical advanced air mobility (AAM) initiatives in the United States.

While some industry influencers argue DFR operations are best run up to 200 feet above ground under shielded conditions (only), we explore the risks of this practice as well as the benefits of extending operational altitude with airspace sensors.